March 29, 2025 - May 03, 2025

White River, South Africa

Click here to view: Zakkie Eloff Exhibition Catalogue

Zakkie Eloff

Centenary Celebration Exhibition

Behind the Canvas - A Life of Work

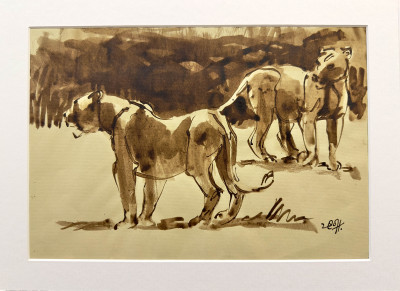

Wildlife artist Zakkie Eloff: Outstanding portrayer of movement and mood

Text by Marguerite Robinson

I

The year 2025 marks the centenary of the birth of Zakkie Eloff, one of South Africa's’ leading fine artists. What he captured on paper or canvas attests to an acute sense of observation, something that was already present from a very young age and that, ultimately, led to him being described as an outstanding portrayer of movement and mood. Furthermore, he was a true nature lover and conservationist – long before it became fashionable.

Zacharias Eloff, one of 11 children, was born on 31 March 1925 in Steenbokpan, a hamlet close to the banks of the Limpopo River in the Waterberg district. A teacher noticed his talent and interest in wildlife and gave the grade 2 boy a box of watercolours, which he put to good use over weekends at home on the farm Kruispad. Little did the young boy know that the time spent in a hide in the veld, built with the help of a friend and from which he observed and drew animals, would be a prelude to things to come. The keen observer was taking his first artistic steps to become an exceptional draughtsman, an artist who relied exclusively on his sketches and never worked from photographs.

As a true lover of nature in the broadest sense, Zakkie later in life made no secret of his dislike of cities and his need to escape city life to return to his landscape of choice. Pretoria was the first city he had to navigate – starting as a pupil at Oosteind Primary School when his family left the farm and moved to the suburb Arcadia. A subsequent move to the more rural Silverton led to a short-lived period at the Afrikaanse Hoër Seunskool. The only available window to art was attending art classes at the school for girls across the street. This situation was untenable for Zakkie, so he summarily found his way to the nearby Pretoria Boys High. There a huge door opened, with none other than Walter Battiss as his art teacher. Apart from noticing Zakkie’s talent – and once giving him a higher- than-perfect score in a progress report – Battiss introduced his pupils to an array of mediums and techniques and took them on field trips in his search for rock art. Acknowledging his influence, Zakkie once said that Battiss had taught them to truly look at things.

II

In 1946 he enrolled at the Art School of the Witwatersrand Technical College in Johannesburg, where he studied under Maurice van Essche and James and Phyllis Gardner, focussing on painting and sculpture. Owing to the lack of a suitable foundry in South Africa, his interest gradually shifted and he began concentrating on portraits. Commissioned portraits and the sale of drawings helped Zakkie cover his art-school fees. His stay in Johannesburg lasted four years, three years as a full-time student and one year in a part-time capacity. While working at Gainsborough Galleries, he was instructed in framing, a valuable craft he would put to good use.

After obtaining his diploma from the Witwatersrand Technical College, he returned to Pretoria and settled in Silverton. Forging ahead with his career, he supplemented his income by framing the works of prominent artists, including Battiss, Hendrik Pierneef, Anna Vorster, and Alexis Preller. Sometimes he was compensated with works of art, mostly drawings and watercolours. In this manner, he acquired no fewer than 147 valuable Pierneef works.

He developed a friendship with Pierneef, sometimes joining him on outings in the hills of Brummeria, where Pierneef lived, or further north to Bon Accord to sketch. Drawings from these excursions later inspired paintings created in their respective studios. Pierneef urged him to pay attention to the constantly changing formation of clouds and was impressed by his ability to depict movement in time.

He also accompanied Battiss on his travels, from the Eastern Cape to the Kruger National Park and across borders – from Lesotho to Mozambique.

His first major exhibition was opened on 1 August 1953 by Battiss, who also encouraged him to continue his studies abroad. After his seventh exhibition and with savings of £2 000, Zakkie set off on his next adventure – it was 1956, and he was 31 years old. He enrolled at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London, where he mainly concentrated on drawing, etching, and other forms of graphic art. Apart from learning and mastering new techniques, he enthusiastically visited art galleries and exhibitions. The art of Thomas Gainsborough, James McNeill Whistler, and John Piper particularly inspired him. To make ends meet, he worked as a bank clerk and did a short stint as a garage assistant. Not feeling at home in the big metropolis, he moved from London to Kent.

He travelled extensively in a Volkswagen Beetle – to experience the works of great artists first-hand in European art museums. At the Prado in Madrid, Spain, he was granted special permission to study Francisco Goya’s drawings, stored in a vault. Zakkie was even more convinced that solid draughtsmanship is the foundation of artistic success. In Amsterdam, Netherlands, he spent much time studying Vincent van Gogh. On his return to London, the director of the National Gallery made it possible for him to study art restoration, adding to his numerous abilities.

III

At the end of 1957, back home in South Africa, Zakkie showed renewed interest in etching, lithography, and woodcuts. He greatly appreciated the work of the Japanese woodblock-print masters Hiroshige and Hokusai. From 1958 to 1961 he was involved with the Pretoria Technical College as a lecturer in drawing and graphic art, with colleagues such as Ernst de Jong, Robert Hodgins, and Albert Werth.

His appointment as an “itinerant game ranger” in Etosha National Park in Namibia (then South West Africa) made the great escape from city life possible. His first posting was at Otjovasandu, with René (née Van Zyl, a former student and now his wife) at his side. Fortunately, nobody was home when the young couple’s house burned down after a paraffin refrigerator exploded, destroying an irreplaceable collection of artworks by Battiss, Pierneef, Preller, Adolph Jentsch, and Fritz Krampe. After six months they moved to Halali, where they stayed until 1968.

Zakkie had ample opportunity to study game at close range, taking his sketchbook along wherever he went, with his drawings increasing significantly in volume and quality. Despite a close shave with a snake and a leopard, Zakkie was in his element, more than happy to focus on animals as his subjects: “They do not say my nose is too long, or my ears are too big.” Expressing movement became characteristic of his art, and all species were included in his sketches, monotypes, and paintings from this period. Fortunately, exhibitions in Windhoek and a commission for 10 large paintings from the Directorate of Nature Conservation helped to alleviate the severe loss at Otjovasandu. The works from his Etosha period were colourful and free.

With Zaskia, the eldest child and only daughter, approaching school-going age, the Eloff family, including sons Arend and Phillip, had to consider a new chapter. The practical choice – moving to the property he owned in Pretoria North – held little appeal for Zakkie. He had already proven that living in the city wasn’t necessary to maintain his excellent relationship with E. Schweikerdt, an established art supplier and gallery, which had started during his high-school years. A visit in White River while en route to the Kruger National Park, to the renowned ceramic artist and potter Esias Bosch, a fellow art student from Johannesburg and close friend, supplied the ideal solution. Bosch was building a home and studio on a plot outside town. The surroundings appealed to the Eloffs, who bought the adjacent plot, where they built Ozondusonanandana, meaning “the place where all the game has disappeared” in Ovambo. At the end of 1968, Zakkie made the leap to full-time artist, with René contributing to their livelihood by pursuing her own art and participating in group and solo exhibitions.

At variance with the name of their new home, Zakkie made game come to life in his studio next to the house. The same subject could be captured in various media – the pencil sketch, the pen drawing, a monotype or watercolour, or perhaps an oil painting. He was also the proud owner of a Kimber etching press, broadening possibilities to experiment.